Written by Sam Byrd

I have never used box squats in my training. I have never used good mornings either. Nor I have I ever used the reverse hyper. I tinkered with using chains and bands for a brief period but did not find them as beneficial as purported. I have never even done the Westside or Smolov programs! It would seem that I have avoided doing all the things the powerlifting world believes is necessary to build a big squat. Nevertheless, I have managed to break multiple All-Time World Record Squats over my powerlifting career, both raw and geared. If you are wondering what the secret is, then listen up. It’s no secret at all.

QUALIFICATIONS

It has been a while since I was active in the powerlifting scene so many lifters reading this may not be familiar with my name, so let me take just a minute to qualify myself on the subject. I once held five different All-Time Squat Records, both raw and multi-ply geared, at the same time. Using multiply gear I have squatted five times bodyweight in two different weight classes; I was the first and lightest lifter to squat over 1,000 pounds with 1,050 at 198 pound weight class- the only other 198 lifter to squat over 1,000 Shawn Frankle; I am the lightest lifter to squat 1,100 pounds and still the only lifter to do so in the 220 class; I am was the first and lightest lifter to squat over 1,100 pounds in the 242 class with a 1,108 at 227- the only other 242 lifter to squat over 1,100 is Chuck V. In raw lifting I held the All Time World record in the 220 class with knee wraps with an official 777 and an unofficial 825 in exhibition at the Animal Cage. I currently hold the 220 belt only squat record with 783. Currently, my squat is stronger than ever and I hope to display it on the platform very soon. To put it bluntly, I know Squat, and if you will allow me, I’ll introduce you.

How I train my squat is no secret. I have and will share it with anyone. The problem is, most people don’t listen because they either don’t believe me or because they don’t like what they hear. Fact is, I very rarely squat heavy. The majority of my squat training, I would guess 90% of it, is done with around 420 pounds. That’s right, I built an 800+ belt only raw squat and an 1,100+ geared squat training with only about 420 pounds. Unbelievable? Believe it.

PHILOSOPHY

Much of my training philosophy comes from studying the word of Dr. Squat himself, Fred Hatfield. If you are serious about squatting big but you aren’t familiar with this name, you should be. He was a phenomenal squatter who spent his life studying the science behind the movement and how to use the science to excel at the lift- which he did. I adhere to two core precepts of Dr. Squat’s research: the scientific formula for Power and the principle of Compensatory Acceleration Training (CAT).

Basic high school science can help you determine the right amount of weight to use on the bar by understanding the relationship between force, mass, and acceleration. Remember, Power equals mass x acceleration x distance, all divided by time. That’s right, those four years weren’t a total waste after all. Ehh, who am I kidding- I hated this crap then and I hate it now so I’ll save you some headache and skip all that crap to tell you how the research breaks down. It basically showed that light weights moved to fast to create much power and heavy weights moved to slow. What this means is that the optimal training weights for power and rate of force development fall somewhere between the ranges of 55-85% of maximum effort.

Compensatory Acceleration Training is the idea of increasing force output by accelerating the weight throughout the entire range of the lift. I often see this idea confused with “speed training,” in which the purpose is to move the weight “fast.” However, the idea of CAT is to continue to move the weights FASTER as your leverages in the lift improve. The traditional Westside Method speed day is not the same, primarily because of its focus on accommodating resistance by adding chains and bands to compensate for the improved leverages and make the lift harder at those points. It is not the same. The increased resistance will force you to remain at a constant speed, or worse, slow down, when the goal of CAT is to accelerate all the way to the top.

Now that you have a basic grasp of the “why” of my training, let’s take a look at the “how.”

APPLICATION

Training Poundages

My training poundages are determined by the force curve described above, 55-85% of my max. However, I do not use a percentage of my limit max or contest max. I base my training percentage off my training max. That is, I base the training percentage off a weight I know I can hit on any given day regardless of what else is going on my life- no sleep, sick all week, maxed out on the lift yesterday, or haven’t trained the lift in two months. This is my baseline strength. Brandon Lilly recently termed it his “365 Strength.” Whatever you want to call it, most high-level lifters who are at all tuned in to their body and their training will tell you that this number is about 90% of your most recent contest or limit max. Need further confirmation? A brief glance at three of the top powerlifting programs being utilized today- Jim Wendler’s 5/3/1, Brandon Lilly’s Cube Method, or Chad Wesely Smith’s Juggernaut Method- support my own findings. Each of those programs calculates training poundages based on about 90% of the lifter’s most recent max.

If I have peaked properly for a competition, there is no way I should be able to hit my contest max in the gym. Peaked properly, my contest max should be at or near my absolute limit max. Additionally, my limit max each day or week may change based on what is happening in my life at the time. Some days my actual limit max may be way above my set training max while other days my training max is my limit max. Using a “365 Strong” max allows for those daily and weekly fluctuations.

Sets and Reps

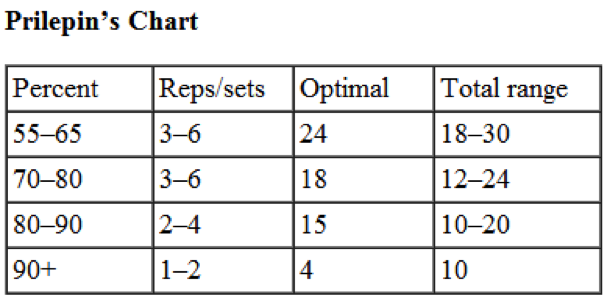

My set and rep schemes are determined using the Prilepin Table. The Prilepin Table is the result of a lot of Russian research done with Olympic weightlifters. It depicts the optimum number and range of reps given a certain percentage to increase strength. The researchers looked at bar speed, technique, and the lifter’s next competition max and developed the following numbers:

The “Percent” column indicates the percent of the lifter’s 1RM. The “Reps/sets” column represents the range of reps that can occur for a single set. The “Optimal” column shows the optimum number of total reps at this percent range to implement a correct dose of stress (fewer reps would be too low a stress, more reps would cause too much stress). The “Total Range” column indicates the lower and higher extremes a lifter could use when lifting in the indicated percent range. For example, the 55-65% row says that a lifter would use three to six reps per set, the optimal rep total is 24 reps, and the range of total reps is from 18 to 30. If the lifter used sets of 3, they could perform 8 sets to achieve the optimal 24 rep total.

I personally use a very basic 5×5 program the majority of the time using weights about 60% of my training max (which is about 90% of limit max). My set/reps do vary when I do increase the weight but I keep things pretty simple. Too many variable and it gets difficult to track what’s working and what’s not.

60% x 5×5 = 25

70% x 5×4 = 20

80% x 5×3= 15

Training Percentages

Most of my training is done with about 60% of my training max. This may or may not be 60% of my max that day, there is no real way to tell. However, I do know there are days when that weight is flying off my back and there are days when it feels slower than a turtle running through peanut butter. On days when the weight is flying I push harder by decreasing my rest times. On days when it seems tougher than it should I increase my rest times. Keep in mind the goal is not just to move the weight, it is to move the weight faster- to accelerate through every rep. Some days there is a lot more acceleration than others but the goal is always the same.

I do not increase the training percentage until I feel I am consistently accelerating bar on every rep. My very last rep should accelerate from the hole to lockout just as fast or faster than the very first rep. I also use this period to increase my conditioning. I manipulate rest intervals before I ever think about adding weight to the bar. If I start out doing 5×5 in 30 minutes, my conditioning sucks. My goal is to first get more explosive- to accelerate every rep. Once I have accomplished that, I begin to reduce rest times between sets. I do not add weight until I can perform all sets within 15 minutes and still feel fresh and invigorated after the last one. Sweaty and slightly winded, yes, but still ready to smash the rest of the session.

I consider this my base building phase, and it can last anywhere from 6-12 weeks. No science here, I just listen to my body. Only then do I consider adding weight to the bar. If you rush this phase or skip ahead to soon it will compromise your future gains. Remember, power is generated by the peed at which you are able to accelerate the weight. A lighter weight must be moved faster to generate the same power as a heavier weight moved slower. So if you skip this critical phase and begin adding weight before you are generating sufficient acceleration and power, your gains will suffer because you will not be able to generate the acceleration and power with a heavier weight either. You must resist the temptation to go heavy. Remember- “More training, less testing.” It may not be flashy but it is effective.

When it is finally time to increase the weight there are no hard and fast rules, but I suggest taking it slow. Ideally, you would re-test your max after 16 weeks and start over based on your new training max. I try to do two 10-12 week rounds before changing training percentages. However, I realize just doing 60% for 5×5 for so long does get boring. When I get bored, the progression I use is fairly simple. It is a 3 or 4 week percentage wave based on a new max that looks like this:

Week 1: 60% of training max @ 5×5 reps

Week 2: 70% @ 5×4 reps

Week 3: 80% @ 5×3 reps

Weeks 4: start over or take a recovery day.

There are times when I just do not want to squat. My body is run down and I would rather go home and eat ice cream. On those days I do just that. No squats, no gym, nothing. This is not an OFF day; it is a RECOVERY day. There is a difference. These days should not come often, and you have to really be in tune with your training to know when to suck it up and put in your work verse when to spend the day recovering. Recovery day can come anywhere in the rotation, just pick up the next week where you left off.

Accessory Day

There are many ways to set up a full power routine based on this training, but I wont get into that now. There are no hard and fast rules. I prefer to do both squats and deadlifts on same day. I alos prefer to do them both twice a week. One back squat day as outlined above, and one front squat day. I always squat first and follow that up with some form of deadlift and finish off with GHRs and maybe abs or calves- but usually not.

CONCLUSION

The goal of this article was to inform you that you can build a big squat without squatting heavy all the time and without the use of conventional special exercises. This is my method. It is scientific and it is simple. It may not be glamorous or revolutionary but it has worked very well for me and I am convinced it will work very well for you too. With more training and less testing, when you do test you will surprise yourself.

Outlining a full routine is beyond the scope of this article. However, I will be releasing a training manual through Juggernaut Training Systems in the Spring of 2014. Until then, mix and match and see what works for you.

Related Articles